As a goat owner, there are a variety of reasons to learn about the anatomy of your chosen herd, depending on your reasons for raising them in the first place (breeding, dairy, wool production, etc.). Whatever your reason for keeping them, understanding goat anatomy is important for maintaining the health and increased productivity of your goats. I could get seriously sciencey here, but that would probably require years of study, so maybe I’ll just slim it down a bit.

Contents

The ‘points’ of the goat

The ‘points’ of the goat are what you’ll be looking at when evaluating newborn kids, or as a prospective buyer looking at breed conformation. We can further break down this external anatomy into five distinct regions: Head/ Neck/ Body (Barrel)/ Forequarters/ Hindquarters.

The ‘points’ of the goat are what you’ll be looking at when evaluating newborn kids, or as a prospective buyer looking at breed conformation. We can further break down this external anatomy into five distinct regions: Head/ Neck/ Body (Barrel)/ Forequarters/ Hindquarters.

Looking at each point individually would take a blog post all of its own, so let’s just look at some essential features you may not have heard of:

Head crest: Between the base of the horns. The forehead is located below the head crest and above the level of the eyes. It’s a flat, bulging shape, if that makes any sense.

Poll: The bulging portion is known as the poll. Found at the top middle of the forehead.

Neck Crest: The upper portion of the neck between the head crest and wither.

Dewlap: A hanging loose, wavy fold of skin between chain and brisket that can be found only in some goat breeds.

Brisket: Between and in front of the forelimbs of the goat, a fleshy mass. You might find a jugular groove running down the neck above the trachea of a goat.

Heart Girth: The circular measurement at the chest of the goat.

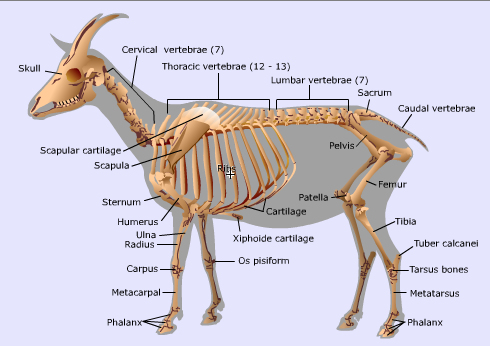

Skeletal Structure

The goat’s skeletal structure can also be separated into main parts: vertebral column, ribs and skull; limbs; and joints.

Vertebral column: Made up of irregularly shaped bones, some fixed and some movable. Cervical (neck) vertebrae, thoracic (chest) vertebrae, lumbar vertebrae, sacral (pelvic) vertebrae and lastly coccygeal (tail ) vertebrae.

Ribs: Elongated, curved bones forming a ribcage, the skeleton of the thoracic cavity (chest). There are 13 pairs of ribs attached to each side of the thoracic vertebrae, mostly fixed to the sternum (breastbone), with the final two pairs not attached (known as floating ribs).

Skull: All the bones of the head. There are a number of flat bones which form immovable joints, mostly disappearing with age; and a lower jawbone (mandible), that forms movable joints with the other parts of the skull.

Limbs: Thoracic limbs (forelegs) and pelvic limbs (hind legs). The forelegs consist of shoulder, forearm and a lower limb. The hind legs are made up of the pelvic girdle, thigh, and a lower limb.

Joints: Where two bones meet. We can put the joints into two main categories: Fixed: with no joint cavity, connected by fibrous tissue or cartilage. Movable: a cavity is surrounded by a joint capsule, with cartilages between the bones to reduce friction and absorb concussion.

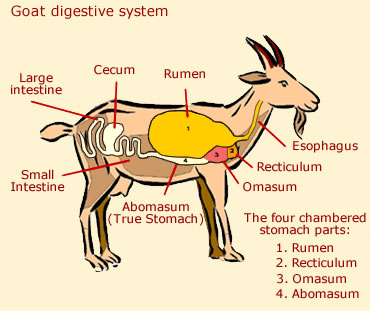

Digestive System

Mature goats are ruminants, which means they chew the cud regurgitated from their rumen. They have digestive tracts similar to cattle, sheep and deer, which consist of the mouth, oesophagus, four stomach compartments, small intestine and large intestine. As with other ruminants, goats have no upper incisor or canine teeth but instead depend on a dental pad in front of the hard palate, lower incisor teeth, lips and the tongue to take food into their mouths.

The Four Chambered Stomach

Rumen: Capacity in goats ranging from 3 to 6 gallons depending on feed. Also known as the ‘paunch’, this is the largest of the four stomach compartments, containing a vast array of microorganisms (bacteria and protozoa) which supply enzymes to breakdown fibre and other food that the goat eats. Cellulose in the feed is converted into volatile fatty acids (acetic, propionic, and butyric acids) as a result of microbiological activity in the rumen, which are then absorbed through the rumen wall to provide up to 80 percent of the total energy requirements of the goat. This kind of microbial digestion in the rumen is the main reason why ruminant animals effectively utilise fibrous feeds and can be maintained primarily on roughages.

Reticulum: Capacity in goats between 0.25 to 0.50 gallons. Also known as the ‘hardware stomach’ or ‘honeycomb’, the reticulum is located just below the entrance of the oesophagus into the stomach. It is part of the rumen separated by an overflow connection known as the ‘rumino-reticular fold’.

Omasum: Capacity in goats approximately 0.25 gallons. Also known as the ‘manyplies’, this compartment has many folds or layers of tissue that grind up feed ingesta and remove some of the water.

Abomasum: Capacity in goats approximately one gallon. Often considered the ‘true stomach’ of ruminant animals, the abomasum functions similarly to human stomachs in that it contains hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes to breakdown food particles before they enter the small intestine.

Food is chewed and swallowed by the goat before it enters the rumen where it is partially digested. Through the process of digestion, food is layered into solid and liquid matter, with solid matter travelling to the reticulum where it is regurgitated (cud) so the goat can mix undigested solids with saliva. When the goat swallows the cud again, it enters the omasum for further processing, before moving to the abomasum and onto the small and large intestines and out through the anus. Liquids are processed into urine and exit through the urethra. Goat poop exits as round, dry little pellets, similar to rabbit pellets.

Reproductive system

This may come as a surprise, but we will need to look separately at the male and female reproductive systems. In case you were wondering, the same applies for every animal on the planet, just so as you know.

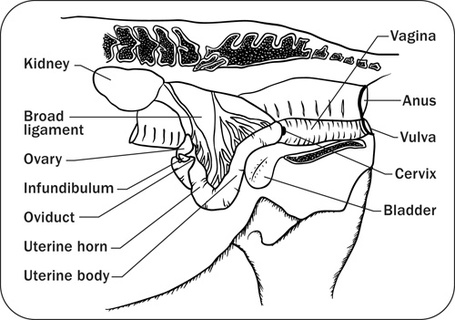

Doe (Female)

Vulva: The external part of the female genitalia. It is pinkish grey in colour and seals the opening of the reproductive system to protect against contamination and prevent sensitive internal tissues from drying out.

Vagina: The vulva leads to the vagina, a tubular structure with a smooth, moist, glistening lining that is tough and covered with mucus to withstand possible injury and bacterial contamination resulting from natural service.

Cervix: A series of muscular ridges forming a protective block between the uterus (and the developing foetus) and the exterior. A cervical plug of mucus keeps out harmful bacteria, foreign debris and undesirable fluids. This plug seals the cervix during pregnancy and when the doe is not on heat.

Uterus: Commonly known as the womb, when the doe is not pregnant, the uterus is 2–3 cm long with two horns extending from it. The lining is covered with tiny blood vessels which provide nutrients for the growing embryo. Small raised areas on the uterine wall (Caruncles) are attachment points for the placenta, whilst the horns are linked by a thin, weblike ligament. These separate and taper off into the fallopian tubes before leading to the ovaries.

Ovaries: Attached by funnel-shaped structures called infundibula, the infundibula and the fallopian tubes are lined with tiny, hair-like projections that wave in unison to create currents in the flow of mucus. The sperm find the egg by swimming directly against this current.

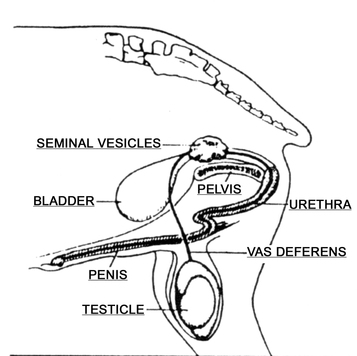

Buck (Male)

The uncastrated buck has two large testicles between the legs which produce semen to impregnate does. A castrated buck is called a wether, the testicles removed either by banding or surgical procedure so the buck can no longer reproduce.

The penis of the buck is sheathed inside the body and extends outside for reproduction, or when the buck is excited and urinating. The male goat’s penis is extremely long and extends towards the front legs. Males regularly urinate on the backs of their legs and on their beards and in their mouths when they are excited, so don’t worry if you see your buck does this, it is normal (but weird at the same time). It generates a strong odour to attract females, and yes, it stinks. Let’s just say Eau de Buck won’t be hitting the shops anytime soon, unless it’s one of those shops only consenting adults of legal age attend.

Ultimately, this really has been a short overview of the anatomy of your goat, but if you wanted to go deeper the NSW government has an excellent factsheet:

https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/178336/Anatomy-and-physiology-of-the-goat.pdf

Or check out these websites: